SITES AND COMMUNITIES

_edited.png)

_edited.png)

GUAJIRA

Riohacha, Manaure y Maicao

Koushalai, Tutchonka,

Ipamana, Isashimana, La Plazoleta.

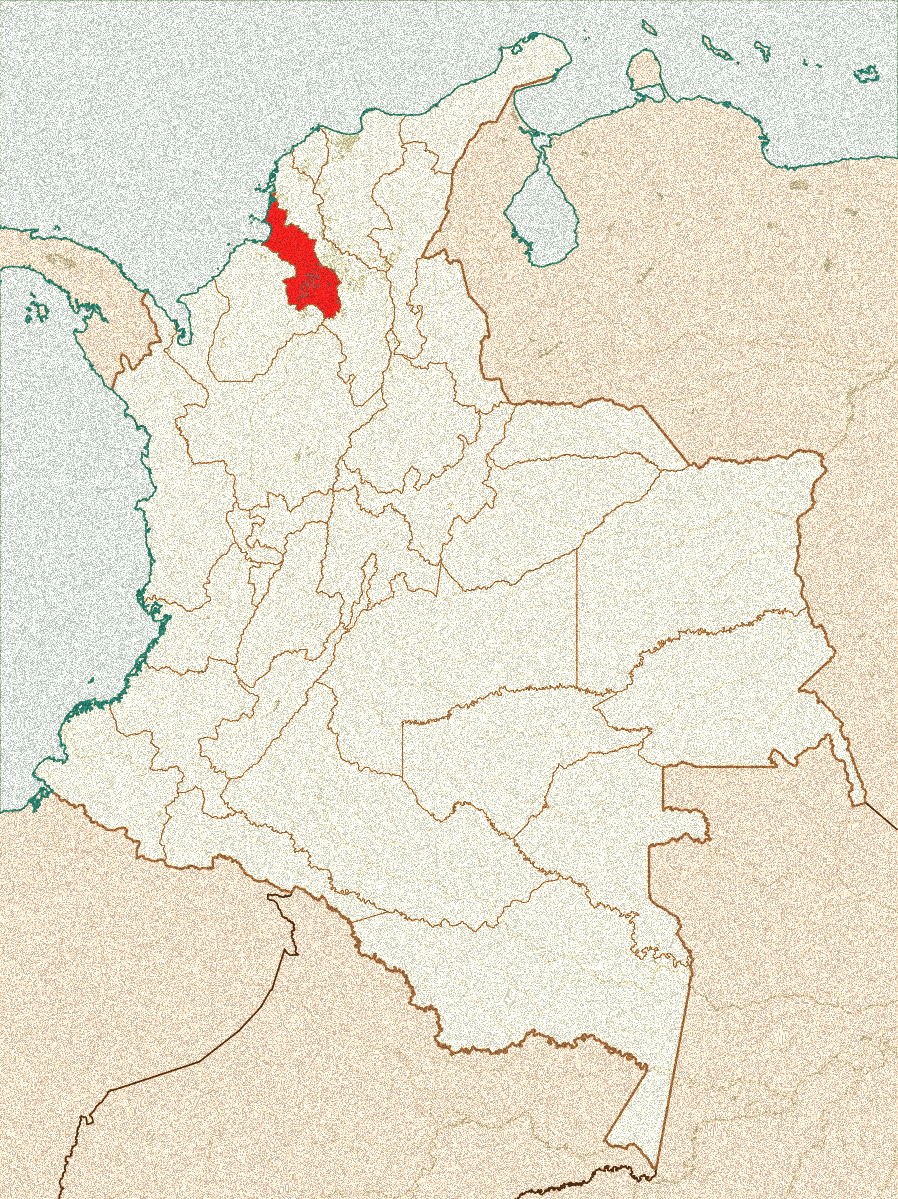

SUCRE

Corozal, Sampués y

Morroa

VillaLuci, Sabanalarga y Las Llanadas.

CHOCÓ

Cuenca del Río Atrato

Río Quito, Quibdó, Medio Atrato y Cantón de San Pablo.

GUAJIRA

La Guajira, located at the northernmost tip of Colombia, is one of the most arid territories and, at the same time, one of the richest in natural resources. However, the region faces a structural water crisis that directly affects Indigenous and rural communities, especially the Wayuu people. Their ancestral water-management practices have been displaced by extractive models and fragmented state policies that do not guarantee equitable access to the resource.

The water deficit is driven by climatic factors—such as prolonged droughts and irregular rainfall—and by the overexploitation of water sources, particularly the Ranchería River, geared toward mining activity. Meanwhile, thousands of families depend on hand-dug reservoirs (jagüeyes), windmills in disrepair, or sporadic water trucks dispatched by the state. This situation not only constrains daily life but has also led to child malnutrition, waterborne diseases, and the weakening of the Wayuu community fabric.

Policies implemented, such as the Guajira Azul Plan (2018), have produced limited results due to weak institutional coordination and a lack of intercultural dialogue. In this context, water scarcity cannot be understood solely as an environmental problem but as a historical and political phenomenon. Overcoming it requires recognizing the cultural value of water and strengthening community management systems, moving toward water governance that integrates the voices and knowledge of the Wayuu people.

SUCRE

Sucre experiences contrasting water realities. In La Mojana, water is abundant during flood seasons but safe water is lacking during low-flow periods; on the Gulf of Morrosquillo coast and in the Montes de María, seasonal deficits, tourism pressure, and salinization strain water sources. Scarcity is primarily functional: the resource exists, but quality, infrastructure, and management fall short. Degradation from pathogens, sediments, nutrients, and salinity predominates, alongside insufficient sanitation. Added to this is a high dependence on aquifers—especially in the savanna and the coastal strip—which are threatened by overexploitation and saltwater intrusion. Urbanization and gray infrastructure, by disconnecting the territory from its natural hydrological dynamics, exacerbate the problem.

The consequences for health and the economy are clear: more waterborne diseases and post-flood outbreaks; turbid or saline water even in schools; flood losses to housing, crops, and livestock; declines in fisheries; impacts on tourism due to poor beach quality; and high supply costs (water trucks, pumping, household treatments) that burden households, especially women and girls.

The response requires inter-institutional coordination with intercultural dialogue at its core. Key actors include the Ministry of Housing (MinVivienda), the National Unit for Disaster Risk Management (UNGRD), the Ministry of Environment and IDEAM, and CARSUCRE—in coordination with CARDIQUE and CVS—together with the departmental government and municipalities. For this coordination to work, Afro community councils and Zenú cabildos must serve as co-decision-makers in permanent water roundtables; prior consultation must include cultural mediation and define shared responsibilities for operation and maintenance; and the co-production of knowledge—community water-quality monitoring, mapping of aquifers and recharge zones, and records of floods and low-flow periods—must be effectively integrated into official planning.

CHOCÓ

We examine the governance of water as a common good in the middle basin of the Atrato River in Chocó, and the river’s centrality to the life, identity, and mobility of Afro-Atrato communities. The Atrato is over 650 kilometers long and is a source of life for the ecosystems of the Chocó biogeographic region while also supplying water for drinking and domestic uses. It also carries food, patients, and medicines and serves as the backbone of transportation; its degradation undermines fisheries (declines/migrations of species), hunting, travel times and costs, and, more broadly, food security and local incomes. When the river is degraded, all community life suffers.

The project conceptualizes water scarcity as functional: there is no physical shortage of water; rather, safe water is lacking due to degraded quality and the absence of water and sanitation infrastructure, coupled with extractive practices that reduce the reserves available for daily life. In many communities, the same source is used both for drinking and for wastewater discharge, creating a cycle of contamination. Pollution compromises potability, creates shortages, and is associated with disease; the project seeks to document the perception that “environmental suffering equals community suffering,” and it notes the risks posed by heavy metals.

Constitutional Court ruling T-622 of 2016 recognizes the Atrato as a subject of rights and created the Guardians Commission; the ruling aligns with Law 99 of 1993 (MinAmbiente, IIAP, and regional environmental authorities—CARs—such as Codechocó) and Law 70 of 1993 (Community Councils). This opens space for co-governance of water with Black communities. In this context, ethno-biocultural governance comes into play, with a set of formal and informal rules that regulate uses of the river and strengthen local legitimacy.